A couple of years ago, I hiked to the bottom of the Grand Canyon and back with my guy. It was in late June. It was hot. Really hot. At one point, the temperature gauge at the bottom read 146 degrees (when you factor in the heat radiating off the canyon walls). Fortunately, there’s water down there – that famous Colorado River. We plunked ourselves down in it, clothes and all, and cooled off.

It was so incredibly refreshing. The next day when we began our hike out at three in the morning it was already 80 degrees. The word interminable floated through my head as I quite often and wistfully thought about that cooling soak while traipsing along the final few miles of switchbacks to the top. It just kept getting hotter. I had my eye on the water bottle in front of me hanging off my guy’s backpack. It was like a mirage in the middle of a desert, calling me to keep going. I did – to the water fountain at the Bright Angle Trailhead where I doused my hallucinations.

There’s just something about water … even the thought of water … that’s so restorative. As a life-long Californian, the Pacific Ocean has always been part of my neighborhood. I can’t imagine not being able to get my feet wet or beachcomb along its shore. Its presence has, throughout the years, affected my moods, been a source of inspiration and made my hair frizzy … ok, that part’s not my favorite, but I’ll take the other two.

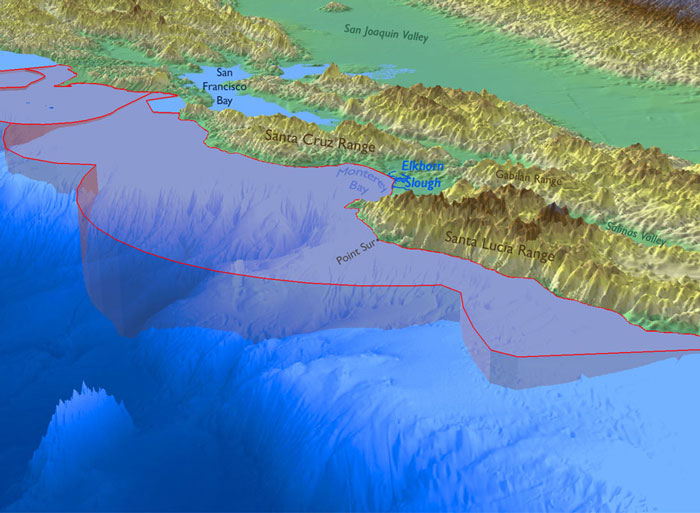

For the past two decades, I’ve been fortunate enough to live in close proximity to the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, the largest in our country at 4,601 square nautical miles. It’s been dubbed the Blue Grand Canyon because of similar characteristics to the reddish-brown Grand Canyon, half its size, that I spent close to six hours climbing out of.

While the similarities of these two canyons are fascinating – both were formed by erosion, both are enormous, both were carved by a river (maybe even the same Colorado River) – the Monterey Canyon has some unique dissimilarities that have been quite beneficial for the Central Coast environment.

It’s all about the weather it creates here. I’m not a meteorologist, but here’s my understanding of what happens. This 60-mile long, two-mile deep canyon has really cold nutrient rich water that comes to the surface, known as upwelling, because of the contour of our coastline and coastal winds. This upwelling cools the marine air, creating the fog that so often blankets the Central Coast.

Now, cue the Salinas Valley. The southern end of the valley warms up faster than the area near the shore. When this happens, the rising warm air pulls the cold marine air down the Valley, creating what’s known hereabouts as the thermal rainbow. This sets up some unique weather patterns that affect the agriculture of this region.

And that’s why my Bill-Nye-the-Science-Guy impersonation is important to understand. Farming supports this region, whether it’s lettuce or strawberries or wine grapes. Not only have we become known as the Salad Bowl of the World, we’ve also been named one of the top 10 wine destinations in the world (Wine Enthusiast Magazine, 2013), putting us ahead of northern California’s Napa Valley. Credit certainly goes to the winemakers who figured all this out, planting vineyards that capitalized on the effects of our own “big canyon.”

There’s a statistic at the Grand Canyon that of the 5 million people who visit every year, only one percent ever go below the rim. More than 8 million visitors come to this area every year … most never get in the water and fewer ever go below. I’m in the latter category.

Terra firma … even when it’s blazing hot … is where I want to be.